Ben Weber » CONCERTO op. 32 Piano

CONCERTO op. 32 Piano

CONCERTO op. 32 Piano

Solo pf,vcl obl,winds:1/picc-1-1/bcl-1,hn

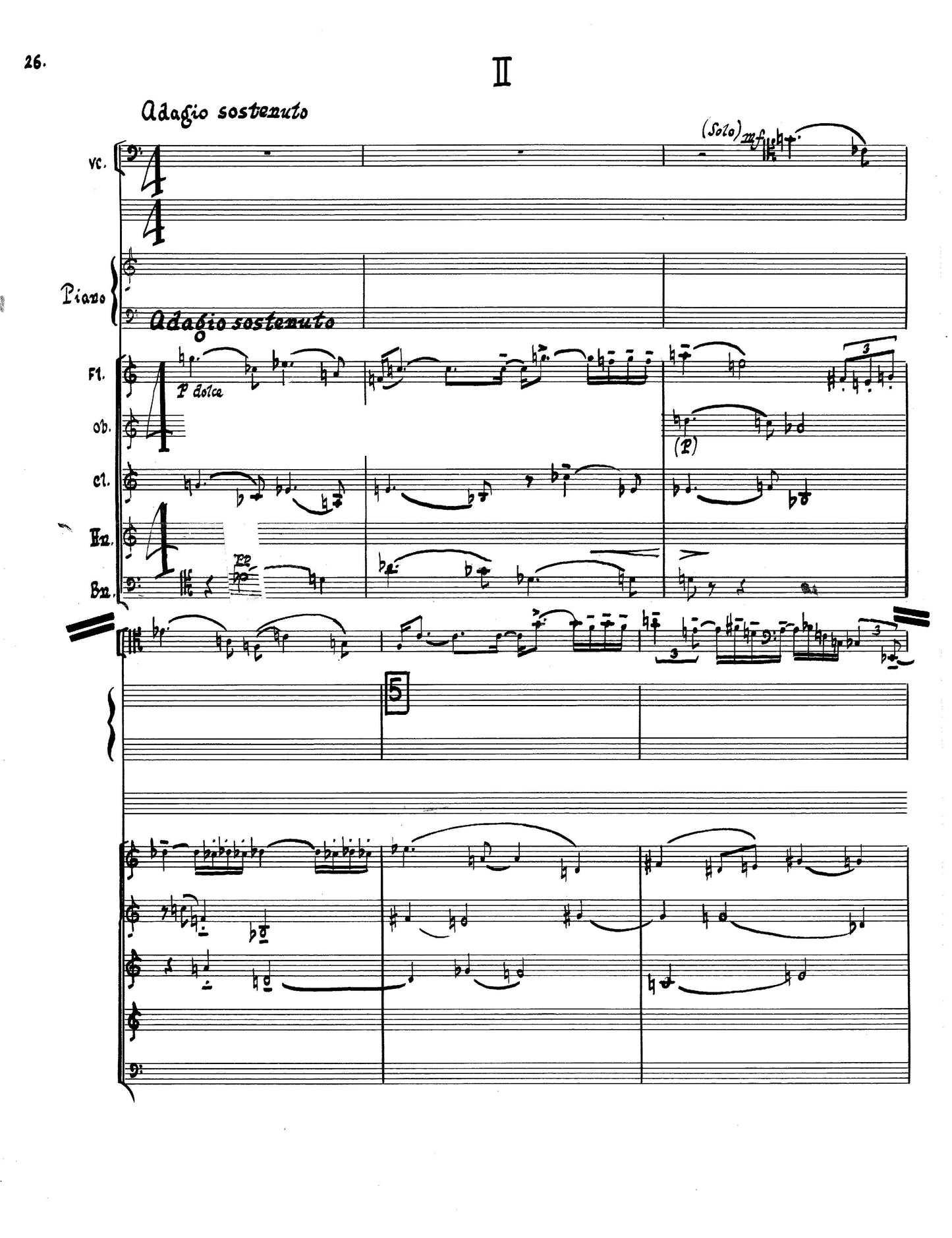

Concerto, opus 32, by Ben Weber, was completed in 1950, and first performed in New York at The New York Times Hall in February of that year. It is scored for piano, cello obbligato, and wind quintet. The word obbligato is here used in the sense of a second solo part"”while the piano is the concerto's soloist, the cello acts as a second solo part, as "essential" (the literal translation of obbligato) to the solo writing as is the piano. The orchestration is unique to Weber, and similar to that used in his Concert Aria After Solomon and the Symphony on Poems of William Blake.

In each of these pieces, the cello is the only string instrument, and in each case, the cello acts as an obbligato voice, participating in an almost constant interplay with the solo instrument or voice. But the cello also serves the function of an entire string section-- a fascinating way of creating the sound of a full orchestra with very economical means. The Concerto was written for pianist William Masselos and cellist Seymour Barab. Both men had a long and meaningful association with Weber's music. Barab knew Weber in his early days in Chicago, where they were part of a musical group that also included composer George Perle and pianist Shirley Rhodes, and 11 some of Weber's earliest works were composed for, and first performed, by Barab.

In 1946, Weber wrote his Fantasia for solo piano for Masselos, and in 1961, Masselos premiered his Piano Concerto with the New York Philharmonic, conducted by Leonard Bernstein. The connection with both musicians lasted throughout Weber's life, and his last completed work, the Capriccios for cello and piano, was also written for these two extraordinary performers. As with most of Weber's music, the Concerto is written with reference to a twelve-tone row, but the harmonies he creates are lush, bittersweet, ambiguous-- and often frankly tonal. (The headline of his New York Times obituary read, paradoxically, Ben Weber, Tonal Composer.) There are sections of dense contrapuntal writing, but they are always written and orchestrated with a transparency and lightness that plays against the complexity of the musical thinking.

The Concerto is a fascinating combination of highly structured form and an almost mystical abandon. He used twelve-tone techniques very much to these ends. In talking about a twelve-tone row, he said that working with a row was like walking into a forest: at first, everything is a blur, but as you enter and walk on, you gradually discover what is most beautiful and most interesting. He used twelve- tone rows in very much the same way that his friend John Cage used chance operations; to move out of conscious thought and to create a music that he hadn't heard before. The structure is never obvious. It's hidden, in an almost Debussy-like way. The music seems to flow out of some completely natural process. And there's an almost alchemical change that happens as you listen, a sort of magical displacement in time and space. It feels as if the music is taking you to one place, and suddenly you're in some other blissful and enchanted world.

The poet Frank O'Hara compared Weber's music to the poetry of Rilke, and said that, in listening to his music, "we realize that what has moved us is a mystery. This music informs us, and its composer, of those things which we are just able to know." ---Roger Trefousse

Authored (or revised): 1950

Duration (minutes): 18.0

Book format: conductor's score

Historic material for this item is held at Special Collections in Performing Arts (SCPA) at the University of Maryland.

SKU

ACA-WEBE-003Subtotal

$81.00Couldn't load pickup availability