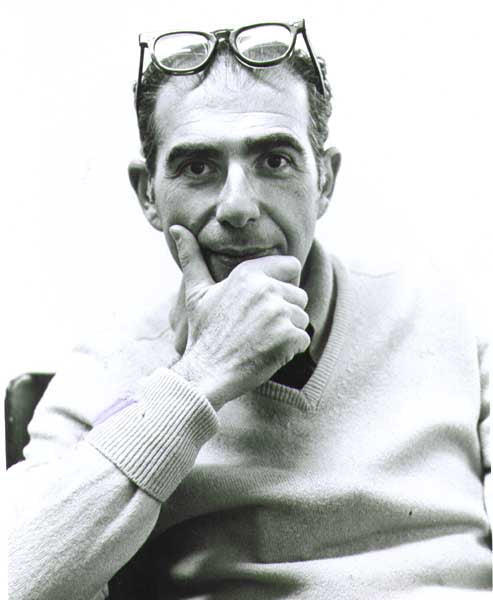

Pleskow, Raoul

1931 - 2022

Raoul Pleskow, composer, was born in 1930 in Vienna, Austria and educated in New York City. His principal teachers in composition were Karol Rathaus, and Otto Luening. Stefan Wolpe was his close friend and colleague. Pleskow has been recipient of many honors, the most recent of which include awards by the National Endowment for the Arts, the Martha Baird Rockefeller Fund for Music, the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

His works have been performed by the Cleveland Philharmonic, the Tanglewood Festival Orchestra, the Plainfield Symphony, the Orchestra de Camera, the South Dakota Symphony, the Pierrot Consort, the Stony Brook Contemporary Chamber Players, the Queens Symphony Orchestra and many others. Commissions include those by the Chamber Players of the Kennedy Center, the Aeolian Chamber Players, the New York Virtuosi, Camarata, the North/South Consonance and the Unitarian Church of All Souls. He was Chairman of the music department at C.W. Post University from the late 1960s until 1994. His work can be found on CRI, Serenus, Ars Nova-Ars Antiqua, Golden Crest, Centaur, CRS, Capstone, and North-South Records.

His music has been published and administered by American Composers Alliance since 1966 and ACA regrets to announce his passing May 18, 2022 in Douglaston, NY.

From Bill Hammel's website 1998

Much of this discussion is derived from discussions with Pleskow as teacher and as friend that go back to about 1963. When I can attribute exactly, I do; otherwise, the reader must understand that what I say is my understanding of what Pleskow has written and has said. As to the authencity of what I say regarding Pleskow's music I can only say that it is a product of those experiences as well as my own personal and independent understandings and observations of the scores themselves. As Pleskow laughingly said to me, "I'm not an authority on my own music."

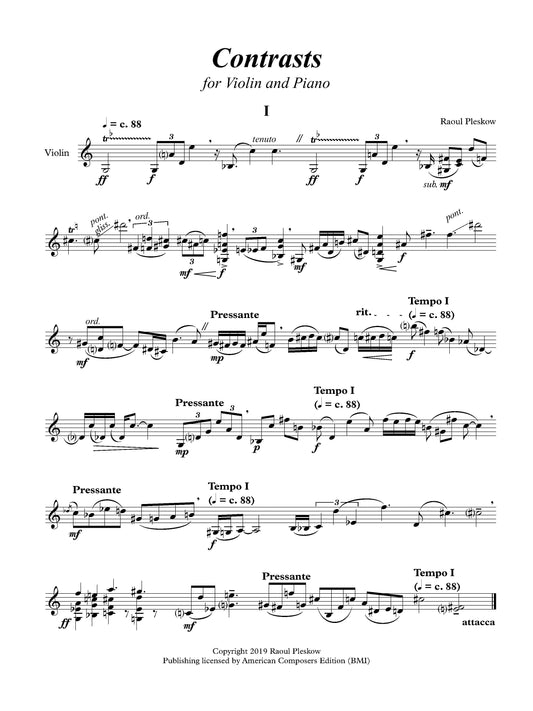

The music of Raoul Pleskow is always a music of contrasting material, but which has evolved to ever higher densities of relationships and lower densities of material whose syntax and semantics is always conscious and referential of the various streams of musical literature from which it arises. This music is never far from song in its attention to lyricism and time, and in its own dramatic telling of itself.

A separate page, [General Remarks on the Music of Raoul Pleskow] describes overall structural consistency while in this page I seek to divide the compositions into three successive periods, by examples showing how they are different.

The following are the three artificially constructed compositional periods which in reality are well connected developments each to the next.

I.

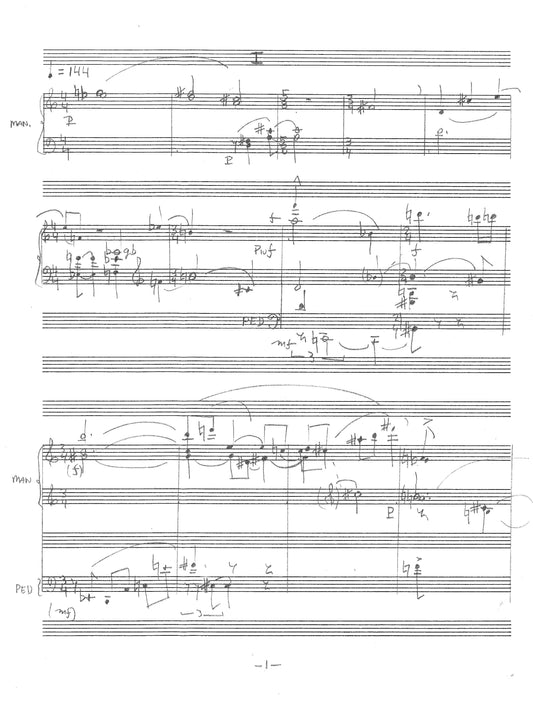

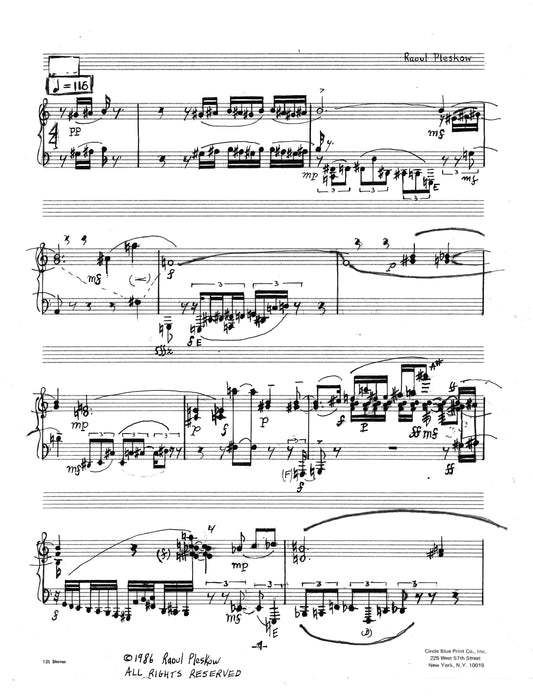

In his earlier works, in a postwebernian atonal idiom, contrasts appear in pitch, duration, sonic density, and tempo in an exuberant, explosive, sometimes violent expressive language that explores extremes. Within these extremes there is always a passionate yet refined lyricism as laconic as that of Webern. While there is a sure consciousness of the circulation of the twelve tones, the material is not serialistic, and avoids any hint of the density relationships in its easy plasticity; rather, the pitch material waxes and wanes as the material undergoes regroupings and exchanges within and between lines and activities. This is a music of exceeding drama, of operatic proportions, though they be chamber works; it enlists the aid of an equally high level of virtuosity. The conscious grouping of pitches as a kind of generalized tonal center begins to appear here. The deft expositions of pitch sets that might seem to have an air of mathematical precision to them, are actually intuitively artistic constructions that give that illusion. They are natural expressions of structure and transformation in the language.

--------------

- [Movement for Oboe, Violin and Piano 1966]

- [Music for 9 players 1967]

- [Piece for Piano 1967]

II.

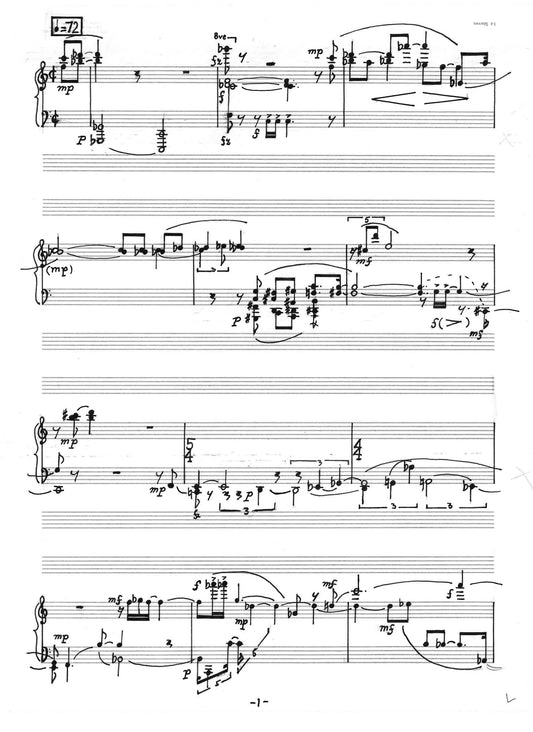

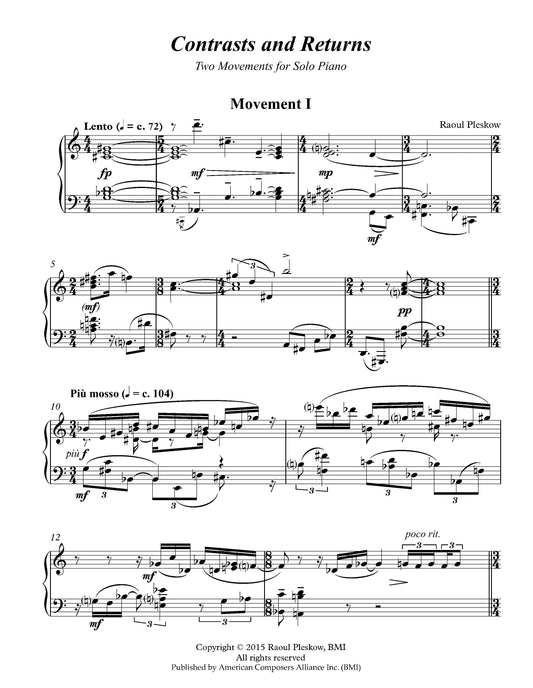

The later works, more than extremes of expressive contrasts, explore new concepts and methods of tonality in a language where tonality and atonality become additional sources of contrast. As in the great tonal period of Western music, the tonal concept here is also the natural wellspring of musical architecture. While the earlier pieces tended to be brief and condensed, forms that are in accordance with an architecture dictated by their atonal nature, now, an emerging tonal coherence brings forth the possibilities of a larger architectural coherence for larger pieces.

- [Motet & Madrigal 1973] [Analysis]

- [Six Brief Verses 1983]

- [Oscar Wilde songs 1987]

III

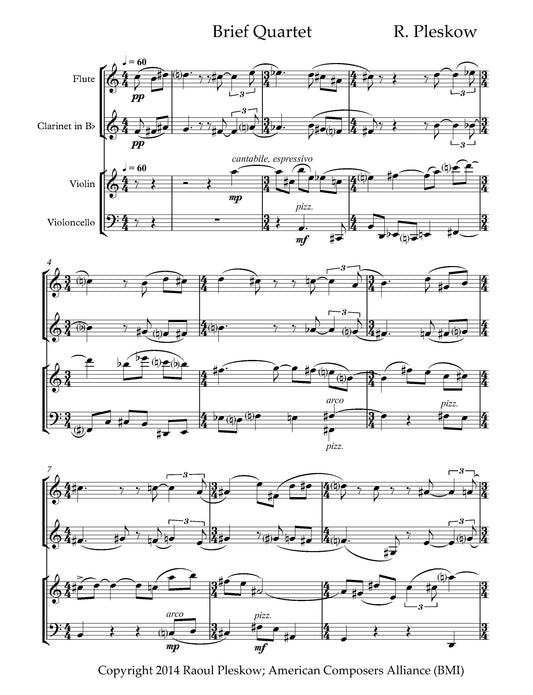

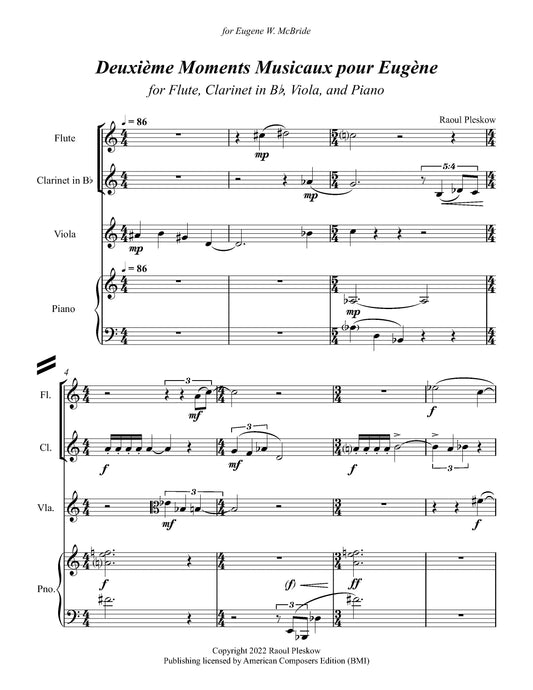

In addition to the creation of the possibilities of larger architectural structures, the emergence of new tonal structures and longer pieces also naturally encourage the development of higher order lyrical structures that can fit within the enlarged timescales where there now also appear subtle allusions to, and illusional snapshots of earlier Medieval music, enriching the perceptual palette even further. Again, this is a contrasting material against echos of earlier compositional passions. While the fire of the earlier works is far from extinguished, the tendency is to explore the newly created lyrical and tonal possibilities within larger structures.

- [On Latin fragments - borders II 1972]

- [Piano Sonatas #1 1989]

- [Piano Sonatas #2 1993]

- [Piano Sonatas #3 1997]

- [Soliloque et Diologue 1998]

- [Piano Sonatas #4 1999]

- [Trio violin, Cello & piano - NEW]

- [Unpublished Sketches]