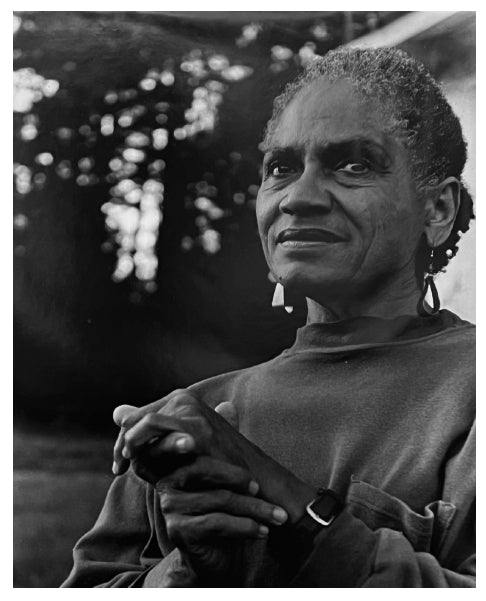

Lee, Consuela

1926 - 2009

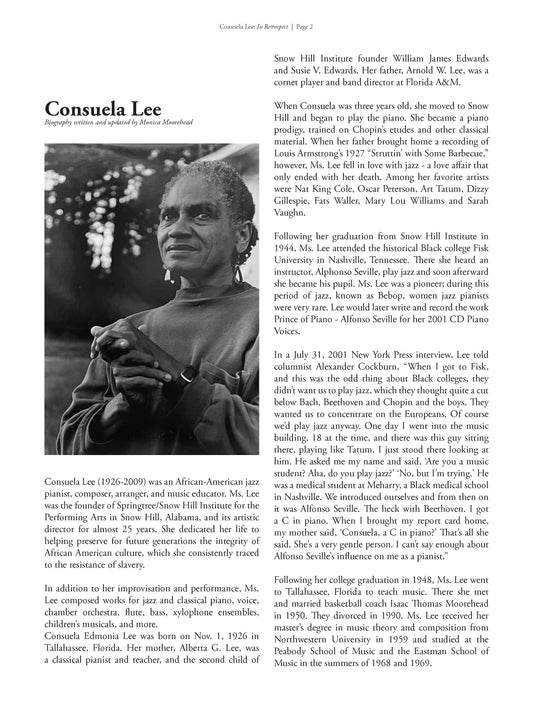

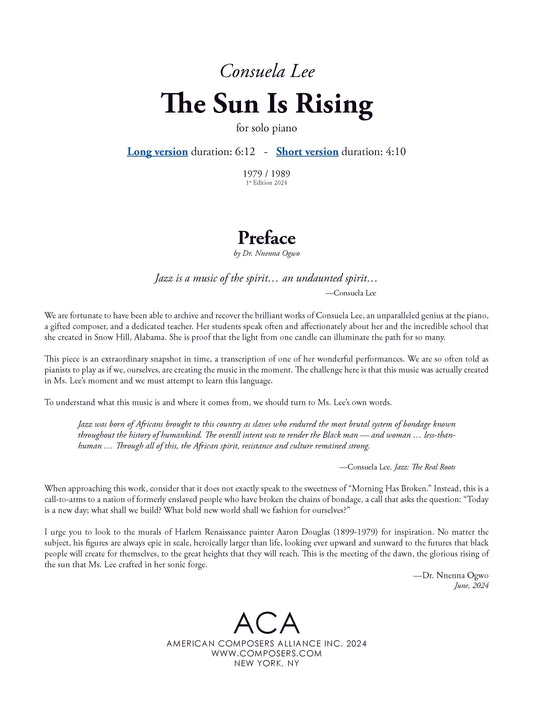

Consuela Lee (1926-2009) was an African-American jazz pianist, composer, arranger, and music educator. Ms. Lee was the founder of Springtree/Snow Hill Institute for the Performing Arts in Snow Hill, Alabama, and its artistic director for almost 25 years. She dedicated her life to helping preserve for future generations the integrity of African American culture, which she consistently traced to the resistance of slavery.

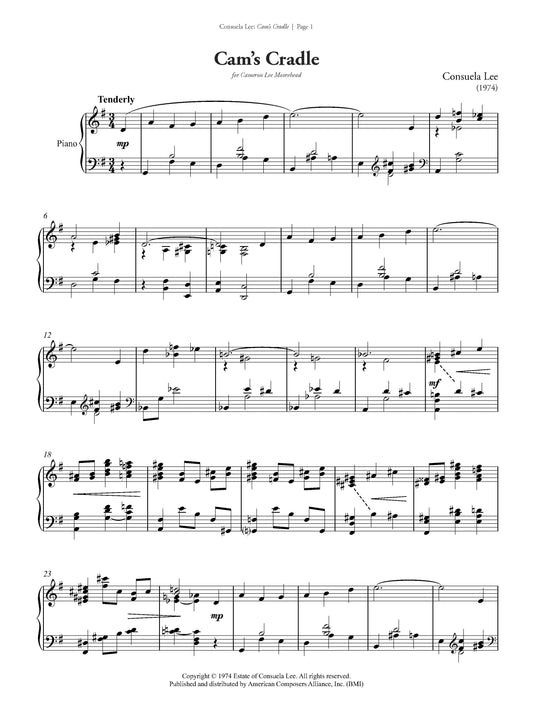

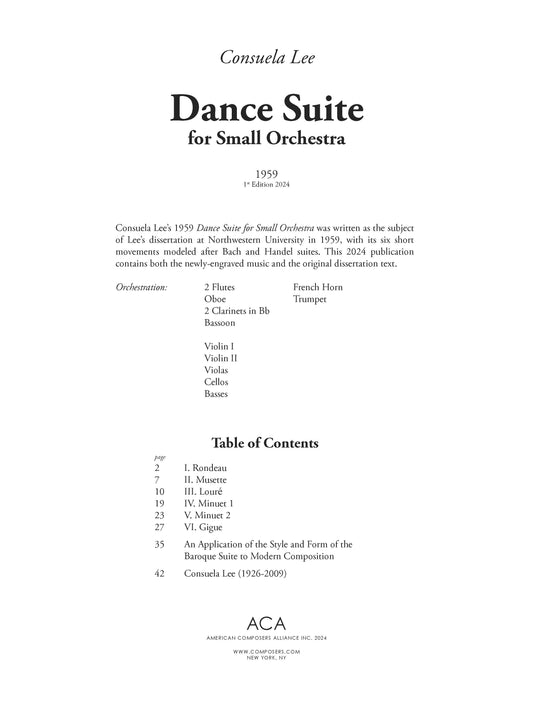

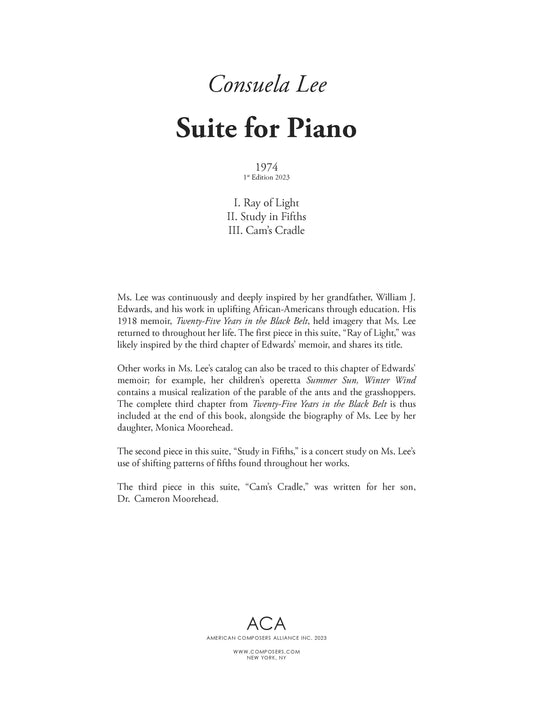

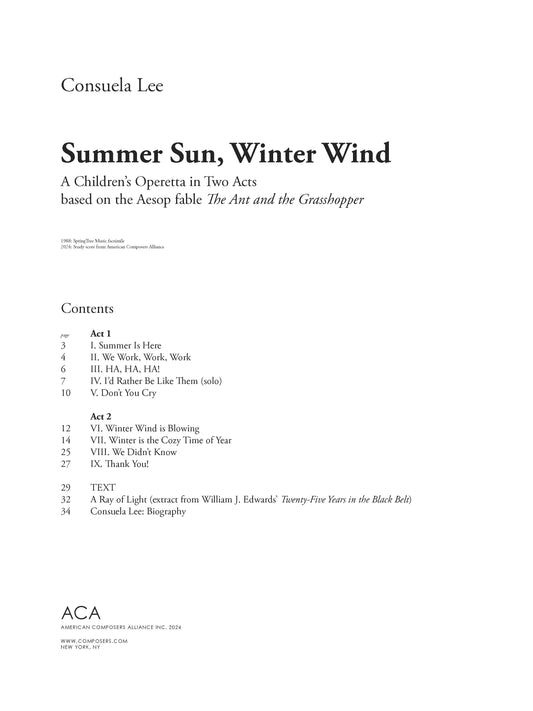

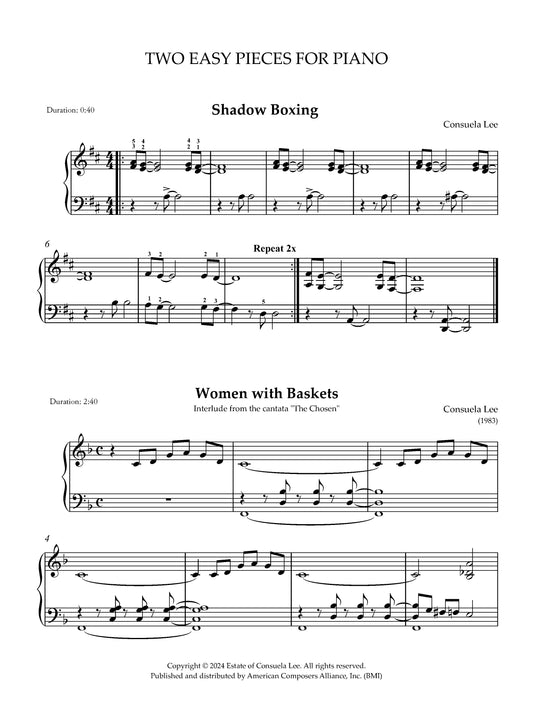

In addition to her improvisation and performance, Ms. Lee composed works for jazz and classical piano, voice, chamber orchestra, flute, bass, xylophone ensembles, children’s musicals, and more.

Consuela Edmonia Lee was born on Nov. 1, 1926 in Tallahassee, Florida. Her mother, Alberta G. Lee, was a classical pianist and teacher, and the second child of Snow Hill Institute founder William James Edwards and Susie V. Edwards. Her father, Arnold W. Lee, was a cornet player and band director at Florida A&M.

When Consuela was three years old, she moved to Snow Hill and began to play the piano. She became a piano prodigy, trained on Chopin’s etudes and other classical material. When her father brought home a recording of Louis Armstrong’s 1927 “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue,” however, Ms. Lee fell in love with jazz - a love affair that only ended with her death. Among her favorite artists were Nat King Cole, Oscar Peterson, Art Tatum, Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Waller, Mary Lou Williams and Sarah Vaughn.

Following her graduation from Snow Hill Institute in 1944, Ms. Lee attended the historical Black college Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. There she heard an instructor, Alphonso Seville, play jazz and soon afterward she became his pupil. Ms. Lee was a pioneer; during this period of jazz, known as Bebop, women jazz pianists were very rare. Lee would later write and record the work Prince of Piano - Alfonso Seville for her 2001 CD Piano Voices.

In a July 31, 2001 New York Press interview, Lee told columnist Alexander Cockburn, “When I got to Fisk, and this was the odd thing about Black colleges, they didn’t want us to play jazz, which they thought quite a cut below Bach, Beethoven and Chopin and the boys. They wanted us to concentrate on the Europeans. Of course we’d play jazz anyway. One day I went into the music building, 18 at the time, and there was this guy sitting there, playing like Tatum. I just stood there looking at him. He asked me my name and said, ‘Are you a music student? Aha, do you play jazz?’ ‘No, but I’m trying.’ He was a medical student at Meharry, a Black medical school in Nashville. We introduced ourselves and from then on it was Alfonso Seville. The heck with Beethoven. I got a C in piano. When I brought my report card home, my mother said, ‘Consuela, a C in piano?’ That’s all she said. She’s a very gentle person. I can’t say enough about Alfonso Seville’s influence on me as a pianist.”

Following her college graduation in 1948, Ms. Lee went to Tallahassee, Florida to teach music. There she met and married basketball coach Isaac Thomas Moorehead in 1950. They divorced in 1990. Ms. Lee received her master’s degree in music theory and composition from Northwestern University in 1959 and studied at the Peabody School of Music and the Eastman School of Music in the summers of 1968 and 1969.

At a Newark, New Jersey nightclub, she unexpectedly accompanied her idol, singer Sarah Vaughn, In the early 1960s, Ms. Lee became choir director of the acclaimed Phillis Wheatley High School Glee Club in Houston, Texas.

In the early 1970s, Ms. Lee and three of her siblings (A. Grace Lee Mims, Bill Lee, and Cliff Lee) formed the musical group The Descendants of Mike and Phoebe, which performed spirituals and jazz on dozens of Black college campuses. Mike and Phoebe were enslaved in Alabama.

Ms. Lee taught at a number of historically Black colleges such as Alabama State, Hampton Institute, Talladega College and Norfolk State University.

Becoming more and more disillusioned with the restraints of college teaching, Ms. Lee decided that the time had come to move back to Snow Hill to teach.

Snow Hill Normal and Industrial Institute was originally founded by Wiliam James Edwards, Ms. Lee’s grandfather, 30 years after the legal end of slavery in 1893, to provide an education and vocational trades to impoverished rural Black people. Today, Wilcox County remains one of the poorest counties in Alabama.

Ms. Lee characterized the Alabama schools as a death sentence for Black children.

The original Snow HIll Institute permanently closed its doors in 1973 due to a desegregation edict. In 1979, Ms. Lee went door to door in the Snow Hill community to poll the residents on whether they wanted to see a school in their community. When the majority voted yes, she left her teaching job at Norfolk State University to reopen her grandfather’s school as Springtree, a performing arts center. Ms. Lee had vowed since the age of 12 that she would one day return home to teach in the Snow Hill community.

Springtree’s main goal was to emphasize the contributions of African Americans to the creative arts, especially through the media of music, drama and dance. Children throughout Wilcox County, from preschool to high school, were encouraged to attend Springtree after their regular classes during the school year and also during the summer months. Ms. Lee also took a job as an artist-in-residence and traveled to schools in various Alabama counties to teach music in schools that had no music programs.

From 1980 until 2003, Snow Hill Day Celebrations included musical programs that attracted the Alabama community and Snow Hill alumni and supporters from throughout the country. These programs were carried out on shoestring budgets, mainly from small grants. In 1981, the Alabama Historical Commission cited Snow Hill Institute as a significant landmark. This recognition led to the federal government officially registering the school in 1995 as an historic site due to Ms. Lee’s efforts to reopen the school.

In 1993, to help commemorate the centennial of the founding of Snow Hill Institute, Ms. Lee’s nephew Spike Lee, legendary folk artist Odetta, and other artists attended. In later years, other major artists such as drummer Max Roach, vibraphonist Milt Jackson, and actors Ruby Dee and Delroy Lindo came to Snow Hill to support Ms. Lee’s work in the community.

Ms. Lee’s students, particularly a group of xylophonists called Bright Glory, toured college campuses, film festivals, and churches around the country to perform her arrangements of popular jazz selections written by Duke Ellington and other famous jazz composers. They appeared in the 1988 WABC’s “Like It Is” TV show hosted by the late Gil Noble in New York City.

Ms. Lee also led a legal campaign to help the Snow hill community win control of more than 1,400 timber-rich acres that her grandfather, William J. Edwards, had bought to begin the school. Corporate interests rake in lucrative profits from cutting timber while the Black community languishes in dire poverty.

She commented in 2006: “The state of Alabama, and the corporate timber interests it is subservient to, have kept the Black community in semi-slavery conditions. Reparations must be paid for the crimes committed against the multi-generations of Black people in Alabama’s Black Belt.”

Consuela Lee was more than just “the world’s greatest musician,” as her brother, bassist Bill Lee, called her. She was a champion for the liberation of Black people, especially in rural areas. She succumbed Dec. 26, 2009, after a three-year battle with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. She is survived by her two children, Monica Moorehead of Jersey City and Dr. Cameron Lee Moorehead of Atlanta, two siblings, cousins, nieces, nephews; loving students, colleagues, and admirers.

Biography written and updated by Monica Moorehead.