Rose, Griffith

1936 - 2016

Composer GRIFFITH ROSE was born in 1936 in Los Angeles. (d. 2016 Paris) His father, Raymond Stanley Rose worked for the New York Stock Exchange, and young Griffith was brought back to New York City before he was a month old. His grandfather was an èmigrè from Scotland, who worked for the railway and had seven sons. Griffith’s mother, New York-born Estelle Marie Wheeler was of English descent. Rose attended boarding schools from the age of about six, including the South Fay School in South Borough, Boston. After the war, his family moved into the Mayfair Hotel at Park Avenue and 65th street in New York City.

His first interest in music surfaced through listening to his mother’s records at home and again when his older sister gave him a recording of Peter and the Wolf. At fourteen or fifteen, he read Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus, and decided at that point to become a composer. In the story, the hero is a fictional composer who invents twelve-tone composition, but goes mad by the end (it was a thinly-disguised portrait of composer Arnold Schoenberg, who actually sued the author). At seventeen, Rose spent a summer at the Bones Brothers Dude Ranch in Birney, Montana, where he learned to mow hay, drink whisky and ride a horse. He also studied Sanskrit while at the ranch, and brought with him a volume of Schirmer’s Contemporary Piano Literature for study.

Rose went to Yale from 1953 to 1954, where he enjoyed a class in ancient Greek poetry. He was “chucked out” as he recalls, from his other three courses —philosophy, chemistry, and German. Rose learned to read music by looking at scores and listening to recordings. He studied carefully the Bartók string quartets, the first symphony of Shostakovich, and an unfinished viola concerto of Bartók, reconstructed from Bartók’s notes by Tibor Serly.

In 1955, Rose studied with Isadore Freed at the Hartt School of Music in Hartford. Rose remembers Freed as amiable and very supportive of the young composer, but dead-set against the Schoenberg style of composition. When Rose told Freed he was relocating to Germany, he was cut off from contact. Being Jewish, Freed couldn’t imagine anyone going to Germany at that time. It was Darmstadt that lured Rose to Europe. His father loaned him the money to buy a Volkswagen, which he picked up in Frankfurt. Rose moved to Germany with his wife Georgene and daughter Adrien, and surveyed schools in Hamburg, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Dusseldorf. Freiburg with its Black Forest was the most scenic, he thought, and the Staatliche Hochschule für Musik itself was also very beautiful. Wolfgang Fortner had come into residence there in 1957, and Rose decided on Freiburg for his continued studies.

Other members of Fortner’s class at Freiburg included Peter Westergaard and Robert Langworthy. Rose recalls, “Fortner was always on the telephone, so we taught ourselves…Westergaard was brilliant”. Rose remembers the arrival of Nam June Paik, a political refugee from Korea, sent by Stockhausen to study composition with the class in Freiburg. Fortner was too conservative for him. Paik rolled marbles, created sounds, and wanted to meet John Cage and go to New York. Rose recalls one of Paik’s pieces at Freiburg involved throwing an egg against the wall. Paik asked Rose to write a letter in English to John Cage to help him make a connection.

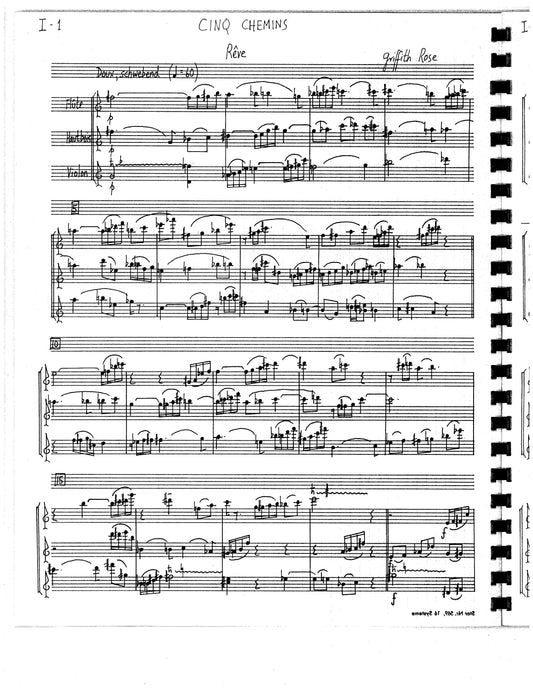

In the summers of 1958 and ‘59, Rose studied at Fontainebleau with Mademoiselle Nadia Boulanger. He moved with his wife, pianist Georgene and two daughters to the village Gouhenans, in France, about two hours from the German border. Paul Sacher had recently brought Pierre Boulez to the Akademie der Musik in Basel. Rose was admitted to Boulez’s class, which he recalls was “very expensive,” and met every two weeks through the winter semesters 1961 to ’62. It was here that Rose met Claude Lefebvre and Louis Andriessen. Rose found Boulez to be extremely severe, like Boulanger, but with a different perspective.

“Both had extreme severity and extreme notions of pedagogy. In Boulanger’s harmony/counterpoint seminar, one had to sing every line through out loud to show it could stand on its own. With Boulez, one had to explain every damn note. He also insisted on flexibility, but not as Schoenberg used it, or it becomes boring.”

Rose recalls that Boulez always insisted his students should refrain from the use of transpositions, and find other systems instead, such as filtration. Le Marteau sans Maître was his most famous work at that time, which was intended, according to Boulez, to sound fluid, not serial. Boulez worked out the elaborate systems he used in Le Marteau (though heavily disguised or buried) with his students in the classes at Basel.

Rose spent the summers of 1961 and ’62 studying with Stockhausen at Darmstadt. A fellow student there was Sylvano Bussotti. Other professors at Darmstadt included Kagel, Cage and Tudor. One of the jokes at Darmstadt was that David Tudor could make a meal for four people using two apples. Rose also recalls lectures by Theodor Adorno that were not well-attended. He recalls Adorno saying to Tudor, who was on the piano faculty, “I am giving a lecture this evening on postserial structuralism, I think it would be interesting if you came.” Tudor coolly answered, “I’m sure it will be very interesting.” Rose thought Adorno “so pompous he didn’t catch the irony…that Tudor had no intention whatsoever of going to the lecture.”

There was no camaraderie between Boulez and Stockhausen, according to Rose. Stockhausen had also broken friendship with Cage. Rose recalls “Stockhausen’s arrogance was incredible,” but concedes that his more flexible approach to composition was a welcome respite after studying under the severity of Boulez.

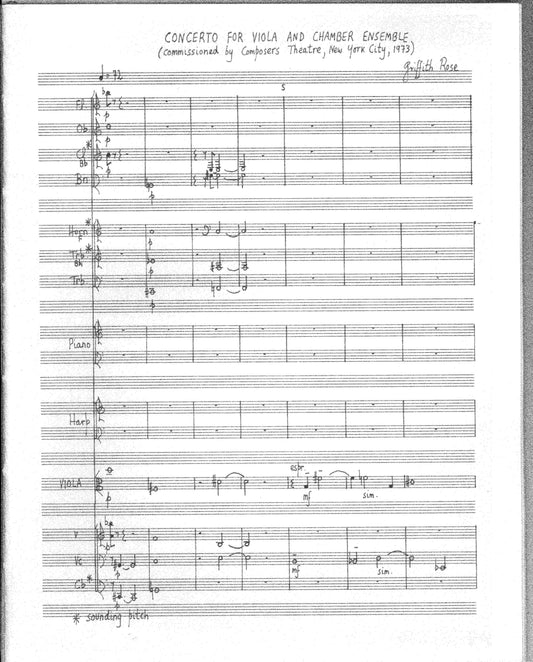

Rose had met conductor Paul Mèfano through Lefebvre in the Boulez class in 1962. When Mèfano saw Rose’s score for his first viola concerto, commissioned by John Watts and the Composers Theatre in New York City, he immediately issued a commande (commission) for a second viola concerto, to be performed by his then newly-formed ensemble 2e2m, based outside of Paris in Champigny. Jack Lang was the cultural minister in France at the time, and Mèfano was encouraging and supportive. A “golden age” of creativity began for Rose with these new connections.

The top-rated ensemble 2e2m premiered many of his works, and he received four commissions from the French state, making him eligible for residency and for membership in SACEM, the performing rights society. One Commande d’Etat would pay up to twelve thousand francs, and there was a SACEM premium paid for all first performances. Though he wasn’t able to live solely from his royalties, he was eligible for the state health insurance, the benefits of which he still enjoys as a resident.

Rose “taught” briefly in Dusseldorf when he was asked to substitute for the class of Manfred Trojahn. He never felt that one could actually “teach” composition, however, and managed to support himself and his family outside of academia.

In 1965, he was divorced from wife Georgene. In July of that year, he moved to Sète, Herault (France). Rose and his friend Bernhardt took turns making dinner for his children, after Georgene had an accident and could no longer cook or take care of them. Rose moved into a 17th-century house with the children; Bernhard and Georgene lived as a couple in the 19th-century manorhouse on the same property.

Rose spent five years in Sète with his second wife, Annick, from 1965-70. They also spent some months in New York City where Rose rented an apartment on Barrow street. In Sète he composed many works. He also met the poet Marie-France Armstrong there.

Rose and Armstrong fell in love at first sight. They left their spouses and eloped to Switzerland. They moved to Cassis, near Marseille, in 1970. The two girls from the marriage to Georgene moved in with them. A third child, Patrick, stayed with his mother Annick.

Griffith Rose and Marie-France Armstrong were married in 1972. They lived happily in various residences in Brignoles, Paris and Venice through 1985, and since then have divided their time between Mèze, in the south, and their house in Paris.

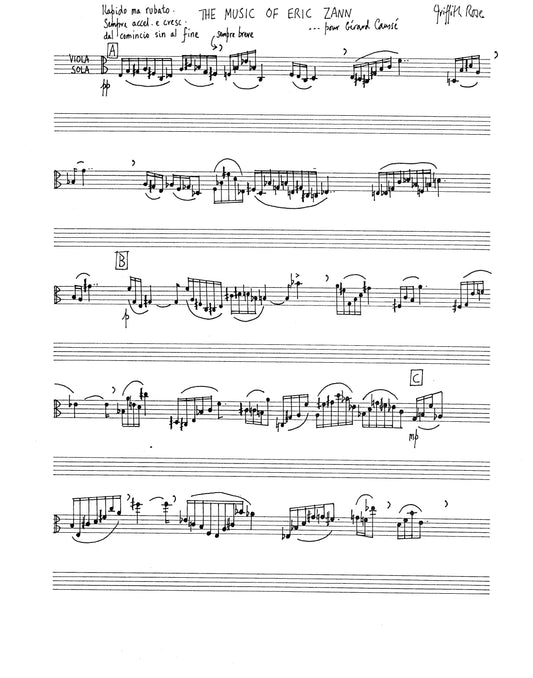

Rose’s musical compositions are encoded with significances that are inaccessible to those who do not possess the key. All of his works are based on a certain fetishism—of numbers, names, lovers, friends, objects, games, works of art, quotations, and other systems of meaning.

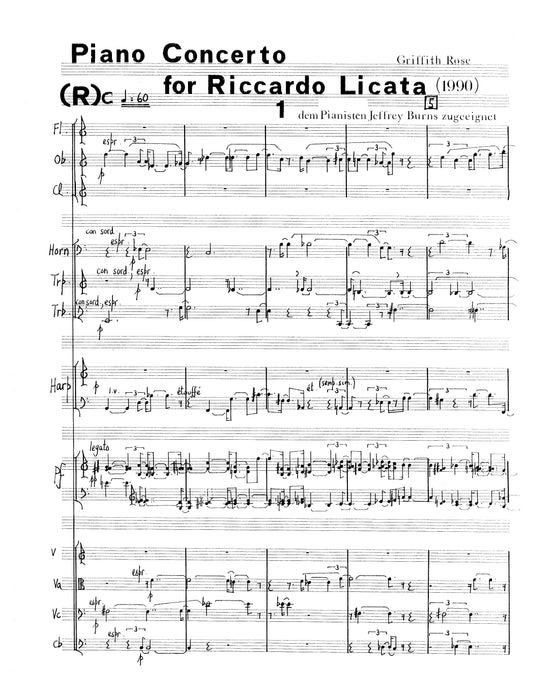

Works of art served to inspire both Ziggurat (a painting by Riccardo Licata) and ,même (the Grand Verre of Marcel Duchamp). Paintings, like poetry have been frequent points of departure for the composer.

“This way,” says Rose, “I already have a structure. In the colors and the forms, the rhythms of the poetry, I find a certain part of the music completely sketched out. Licata and Duchamp are perhaps the only ‘painters’ I have used…but they’re not the only ones who interest me. I would like to do something on Paul Klee, or Carpaccio, my great love of the Renaissance. In actuality, what attracts me to the work of Licata and Duchamp is the geometry. When I set a scene to music, it’s not the impression that I experience while looking at the scene, but rather a detailed geometric reconstruction of the scene itself, retaining its proportions. I take the geometry, leaving aside the figurative or anecdotal elements.”

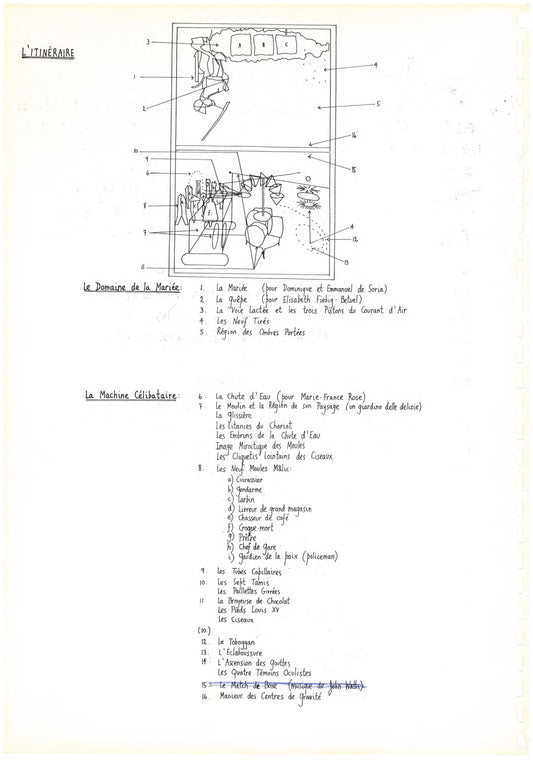

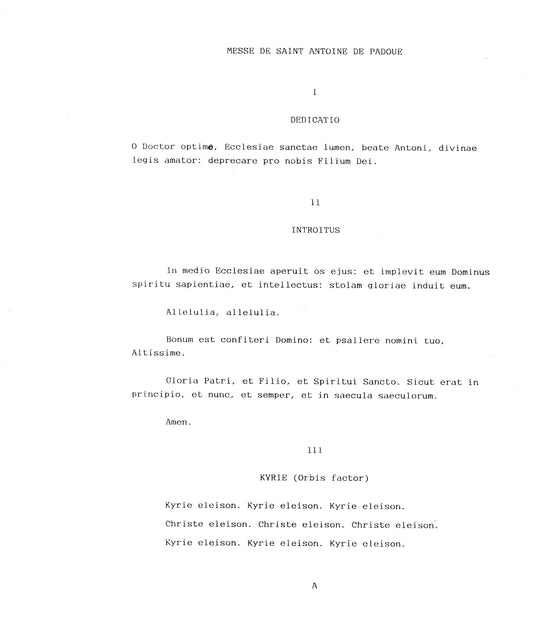

,même is a very elaborate work Rose spent two years composing. It is not only based on the Grand Verre but also on other material Duchamp used in other works. It’s full of systems, allusions and hidden quotations of all kinds. Rose calls it “process composition”. To this process, one can add the exploration of the waterfall near Brignoles, where Rose measured various intensities of water, composing onto the page what amounted to “uninteresting white noise” but also a collection of booklets covered with notes and charts similar to Duchamp’s Livre Vert. The fascination for Duchamp extends to what Rose calls his “ingenious perversity,”—his taste for joking and wordplay.

Rose’s preoccupation with series of numbers constitute the largest part of his compositional output. Arithmetical series and their elaborated combinations represent the ultimate point of his games and enigmatic style. Rose likes to speak of Berg, with whom he shares a truly emotional relationship and predilection for numbers and their mysteries. Similar to listening to Berg, one doesn’t experience formality or dryness when listening to works by Rose. Despite the chromaticism he absorbed with Fortner and the contrapuntal technique from Boulanger, Rose’s works exhibit a lyricism, flexibility, and variety that works in both his tonal and serialized constructions. For Rose, there is no conflict between the structural requirements and lyrical expression. The systems come after the initial idea.

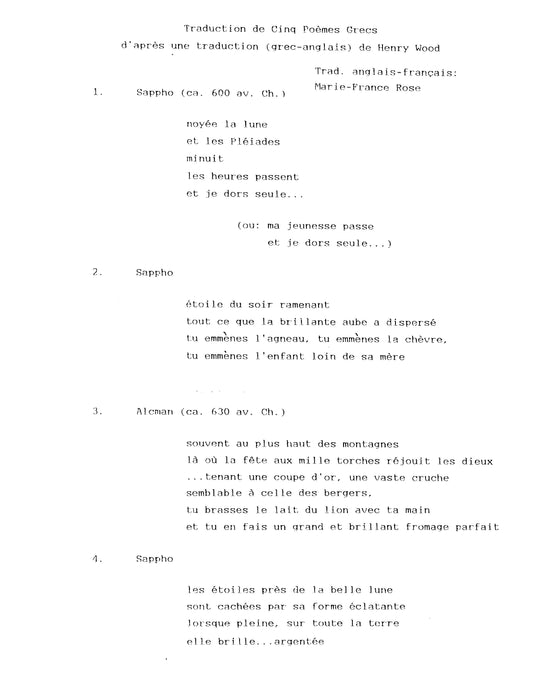

His Five Greek Lyrics (1957) based on Sappho is a very lyrical work. In contrast, he wrote Salpinx (1961) for trumpet and two pianos as a student of Boulez. He recalls and appreciates the harshness with which his professor judged the work: “For many hours I had to explain and justify every note.” Rose experimented with neo-Dada elements and graphic scores after becoming familiar with the works of John Cage, and although random formulations occasionally figure in portions of his works, he ultimately abandoned that path and returned to a more precise, lyrical, systematic technique.

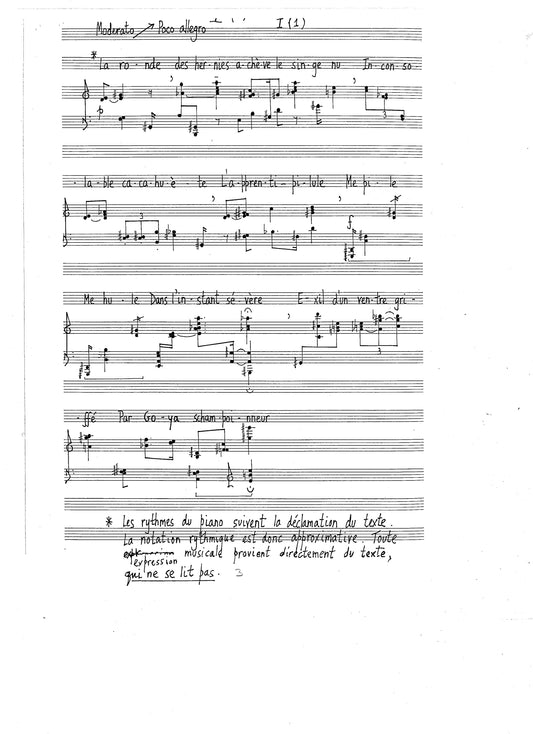

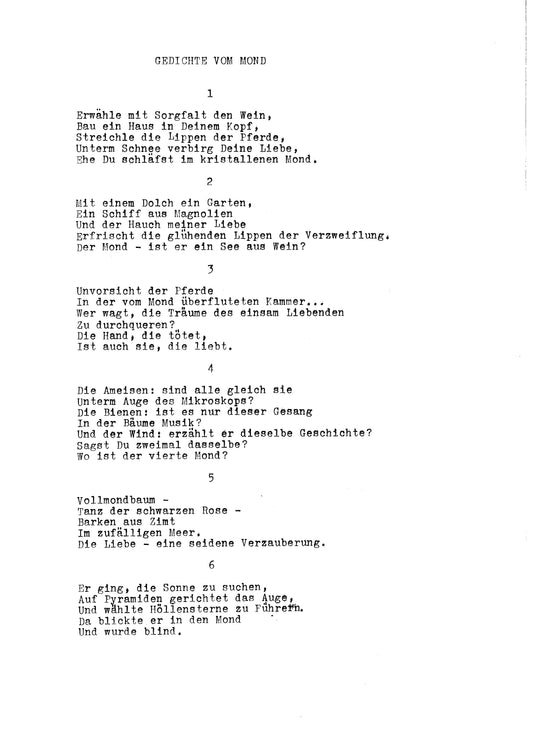

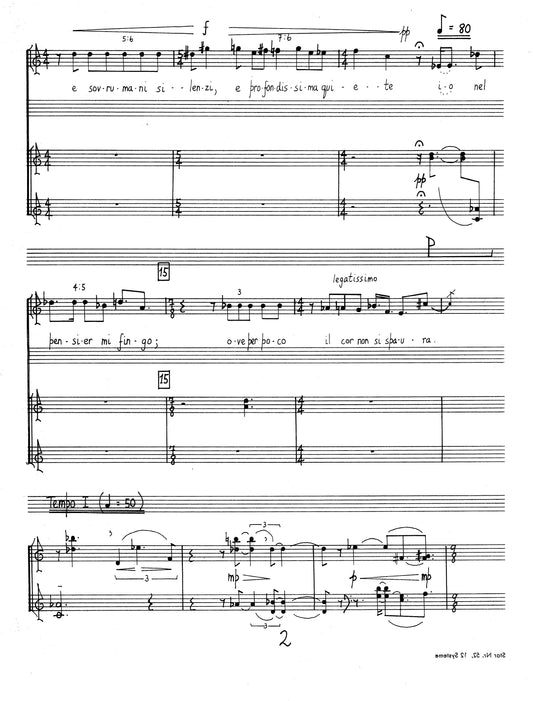

Through the 1970s, settled with his third wife, poetess Marie-France Armstrong, Rose composed the most lyrical and spacious of his works. L’Infinito (1975), written for soprano Maria Licata, wife of the artist Riccardo Licata, that harks back to his early Greek songs, with a pure, lunar quality. Another song cycle, this one for baritone, viola and piano, Gedichte vom Mond (1979) features six poems of Marie-France Rose, and is dedicated to Robert Schumann. Both of Rose’s viola concertos were written in the ‘70s. The first, a commission from John Watts and the Composers Theatre in New York City, ignited a close friendship between Watts, Rose, and Marie-France, which lasted many years.

As a reciprocal gesture of friendship, Rose invited Watts to compose a section of Rose’s new concerto ,même. The section, in order to remain strictly proportional to the area of the “Grand Verre” that it represented, was assigned to be a one-minute interval. During the premiere of ,même, Watts was present to perform his one-minute interval, which became, as Rose recalls, “a grotesque improvisatory digression of eight minutes,” that was poorly received by the German critics in Metz. The friendship between Rose and Watts became severely strained as a result.

,Même features brief quotes of Boulez as well as Francois Couperin. This is the grand work in which Rose reveals the plurality of his style, with the fusion of lyrical, dramatic, numerical, random, polymodality, and quotations. “It is the poetic moment which is the most important,” he said to explain the entrance of each instrument in ,même.

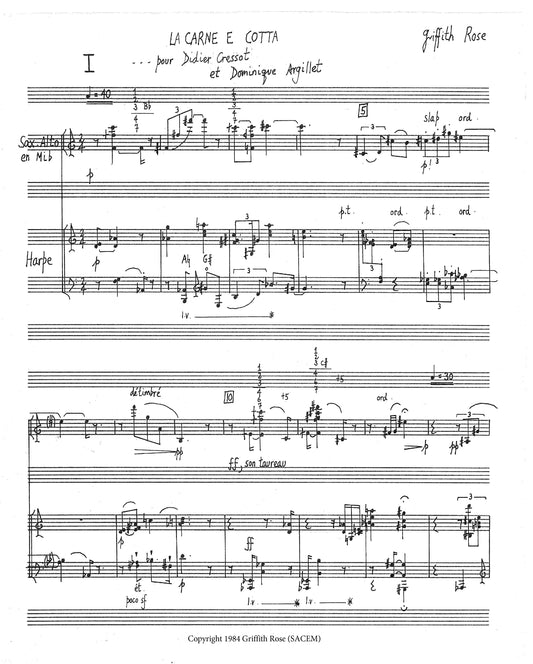

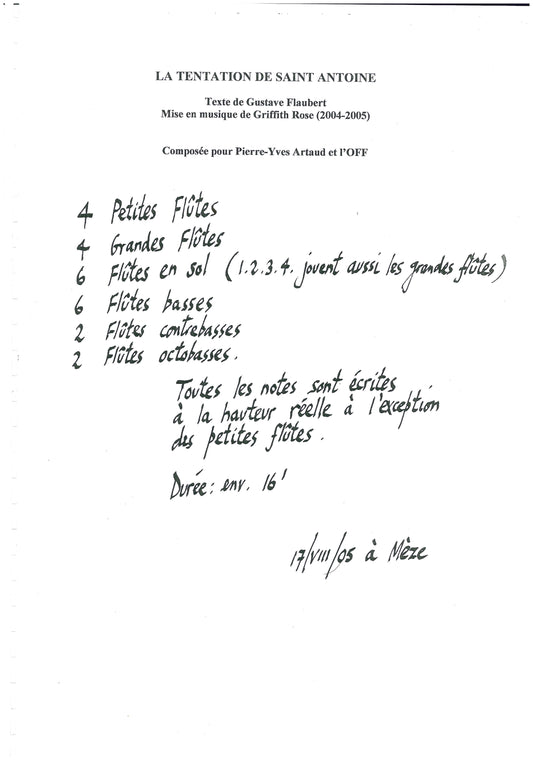

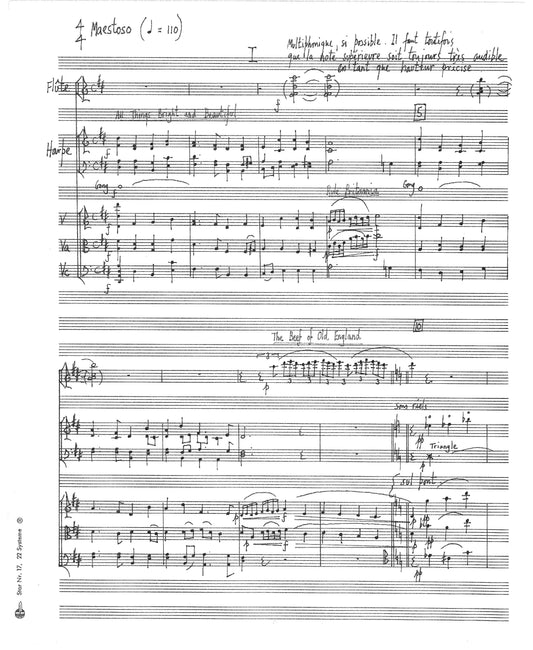

Ziggurat was a commission from flutist Pierre-Yves Artaud. A champion of Rose, Artaud premiered several of his works, including Parergon (1981) and Rhapsodies pour flute (1983). Rose worked out his more thorny serial procedures through the 1980s, with works such as Parergon and Son temps ocèan (1984). In the latter, the soprano is set against a chamber ensemble, in which the instruments are used to the limits of their ranges in complex orchestrations. In contrast, the vocal line is less extreme in range, more legato, and written in arpeggiated gestures and regular rhythms.

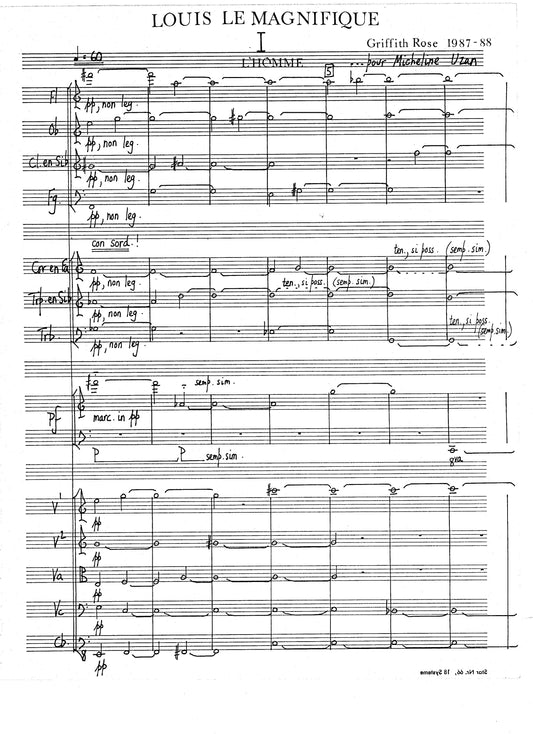

The works of the late 1980s and into the 1990s exhibit some of the most dense textures and complex structures found in the catalog. Rose continued to compose in his studio in surrounded by objects and artworks spanning a long and rich creative life. He passed away on April 12, 2016 at home in Paris.