Watts, John Everett

1929 - 1982

Founder and Director of the Composers Cooperative Society in 1964, and later, the Composers & Choreographers Theater, JOHN WATTS (1929-82) was a member of the faculty at the New School for Social Research in New York City from 1969 until 1982. He directed the Electronic Music Program at the New School and coordinated numerous music workshops, festivals, and concerts there.

Watts was born in Maryville, Tennessee, and began studying music (clarinet) in his early teens. He received his B.A. in Music Composition from the University of Tennessee in 1949, and subsequently entered graduate school there, where he was a student of David Van Vactor and John Krueger in composition, and Alfred Schmied in piano. He won the Thomas Berry Prize for Composition in 1950, but was soon drafted into the army, where he served briefly in the Korean War. He was granted an honorable discharge in 1951 for medical reasons. Watts entered the University of Colorado with a music scholarship in 1951 and graduated with a Masters Degree in Music in 1953.

He was a student of Cecil Effinger in composition, and Paul Parmelee and Howard Waltz in piano. It was there he met the painter Charles Bunnell, and began studies in painting and drawing. He was admitted to the doctoral program in composition at the University of Illinois, where he studied with Burrill Phillips, Robert Kelly, and Robert Palmer. Following the move of his teacher Robert Palmer, Watts left Illinois in 1956 for Cornell University, where he continued to study with Palmer, though Watts became increasingly interested in painting and literature, and lost focus on the doctoral program in music. Taking a leave of absence from Cornell, he was hired by the North Dakota State College in Fargo during the 1956-57 academic year, where he taught Music Appreciation and assisted the Director of Bands.

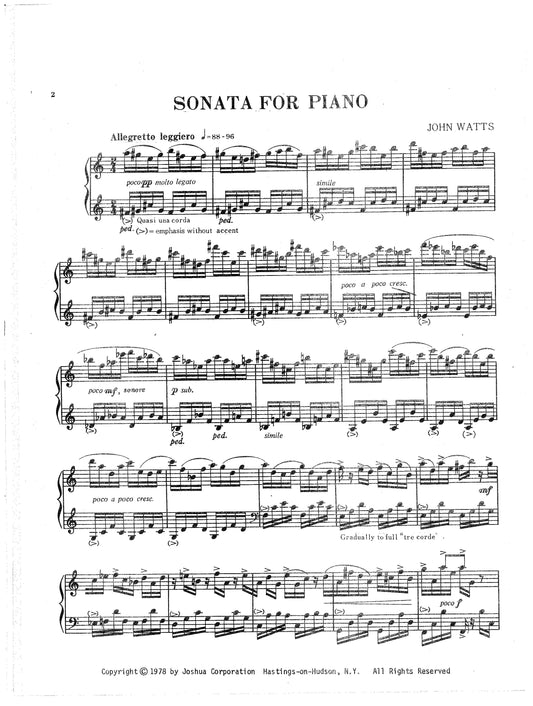

At a summer music festival in 1950, Watts had met the composer Roy Harris, who encouraged him to continue composition studies. After the year of teaching in Fargo, Watts wanted to return to composition, and sought private studies with Harris, then at Indiana University. There, under Harris, Watts began to write Sonata for Piano in 1958, which eventually became his professional debut “break-out” piece some years later when it was premiered at Carnegie Recital Hall by the young gifted pianist David Del Tredici. Invited by his mentor Harris, Watts attended the Inter-American University in San Germán, Puerto Rico during the fall/winter of 1960-61, continuing to work on the sonata, and there made the acquaintance of many performers, including pianist Johanna Harris, and trumpet player Robert Levy.

After studies in San Germán, Watts moved to New York City in 1962 where he worked as a teacher at the Waltann School of Creative Arts in Brooklyn, and as a dance accompanist at the North Shore Community Arts Center. It was during this time that he met dancer-choreographer Laura Foreman. Watts married Foreman in 1963 (his third and her first), in a Unitarian ceremony near Foreman’s mother’s home in Los Angeles. Watts continued to study with Harris informally for several years, and won a residency to the prestigious Yaddo Arts Colony in 1964. With this boost, letters of recommendation from Harris and Robert Palmer, and the strong support of his new wife, Watts attempted readmission to the doctoral program in composition at Cornell in 1964, but his application was rejected.

He rekindled his interest in literary composition and journalism, and found work in New York City as a newspaper editor for the weekly Manhattan East News from 1965 to 1967. He taught music at the Eron Preparatory School from 1965 to 1966, and edited the Journal of Prayer, a non-denominational, inspirational publication from 1967-70. In 1967, Watts returned to musical endeavors, and established an organization for the purpose of presenting concerts of new music.

Initially called the Composer’s Cooperative Society, it soon merged with the Laura Foreman Dance Company to become the Composers and Choreographers Theatre—an entity that quickly grew into a nationally-recognized venue for contemporary music and dance in New York City. The Composers and Choreographers Theatre (CCT) was registered as a non-profit corporation and began an artists-in-residence affiliation with the New School for Social Research in 1969. It was established as a cultural and educational organization specifically to help create a better performance environment for contemporary music and dance, with Watts and Foreman as Co-Directors. At the New School, it developed as one of the first university electronic music/synthesizer programs in the country, created the annual May Festival concert series, and pioneered workshop formats involving composers, musicians, and music and modern dance specialists at work and in concert. Through selective programming, the CCT defined an active creative spectrum ranging from the traditional-based to the avant-garde.

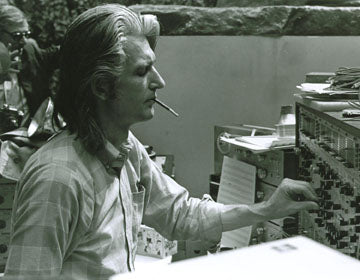

It was a fertile time for discovery of the uses of electronics in music, for the implementation of theatrical elements and performance art in concert, and for the mingling of various art forms, including concert music, modern dance, theatre, photography, film, and early videotape. Watts was introduced to the Moog synthesizer while working with composer Gershon Kingsley at his mid-town studio in the late 1960s. He acquired his own synthesizer in 1970, an ARP, and began performing with it publicly in 1972 with his piece Elegy to Chimney: In Memoriam, for trumpet, tape, and live synthesizer.

Throughout the 1970s, Watts was a composer, an ARP synthesizer soloist, Director of the Composers Theatre, and the Director of the Electronic Music Program at the New School. To the detriment of his composing and performing, he worked very hard to maintain funding sources for the CCT. Overall, the CCT presented the works of more than 200 composers, including 150 premieres and 50 commissions, founded the Composers Festival Orchestra, and produced three LP recordings.

Composers whose works were premiered and performed under the auspices of Composers Theatre include: William Albright, David Amram, Robert Baksa, Warren Benson, Leonard Bernstein, Allan Blank, Alvin Brehm, Earle Brown, Louis Calabro, Robert Clark, David Cope, Mario Davidovsky, David Del Tredici, Roger Hannay, William Hellerman, Gershon Kingsley, Barbara Kolb, Karl Korte, Leo Kraft, Meyer Kupferman, William Mayer, Vincent Persichetti, Quincy Porter, Ned Rorem, Peter Schickele, Elliott Schwartz, Robert Starer, Francis Thorne, Gilbert Trythall, Gerald Warfield, John Watts, Stephan Wolpe, Yehuda Yannay, Ramon Zupko, and many others.

The concerts generally took place at the Studio 58 Playhouse, a salon-theatre on 58th street, seating 125 persons – intimate, informal or formal, and acoustically appropriate for chamber ensemble dimensions emphasized at the CCT concerts. Watts and Foreman were constantly seeking publicity, which could help them generate funds from government, corporate, and private organizations. The most striking publicity they ever received was for a dance concert performance that never actually took place. Jack Anderson’s article in the New York Times (July 1981) shows a poster of the Watts/Foreman presentation Wallwork with a “Sold Out” sign printed across the center. Not happening was the point of the concert, which was advertised—with ticket prices, date, time, and reservation telephone number— on posters all over New York City. When people called the number, they were told that no further names were being added to the waiting list. It was a hoax, though nobody was cheated out of any money. Anderson called it “nutty and annoying,” but he admitted that “it does raise questions about the relationship between art and publicity.”

John’s last performed work, Time Coded Woman, was written for Lukas Foss and the Brooklyn Philharmonic’s “Meet the Moderns” series. It featured video footage by Laura Foreman, with electronic music tracks and orchestra. The pre-flight test premiere took place at Cooper Union on April 2, 1982, and was well-received. The actual premiere at the Brooklyn Academy of Music the following night did not fare well with reviewers. Laura believed that the poor reception of this work—combined with his recent termination from his teaching job at the New School—ultimately contributed to his premature death. Three months after the premiere of Time Coded Woman, he was found dead in his apartment, from what appeared to be complications from chronic alcoholism. ©2002 Gina Genova